Apple, Dolby Labs, and others have been throwing around the phrase spatial audio for several years. It’s a broad term, covering several disparate technologies. On the hardware side, spatial audio with “head tracking” is often gimmicky at best. On the recorded-music side, it’s potentially more interesting. However, quality varies enormously. Turns out a lot of that has to do with how the headphones and earphones interact with each of our own unique physiologies. If only the average consumer could test that out in a consistent and easy-to-understand way.

Well, The Audiophile Society’s Headphone Evaluation and Spatial Audio Test Album aims to let them do just that. It’s a collaboration between audio producer and musician David Chesky and former SoundStage! Solo editor (and current co-host of the Audio Unleashed podcast) Brent Butterworth. The album offers test tracks and songs to help reveal headphone performance. The focus is on spatial audio, but there are additional tests to see how your headphones perform in general.

At $25 (USD), it’s a small price to see how well you, and your gear, can experience spatial audio. You don’t need specific headphones. While the tracks were mixed in a way (multiple ways, in fact—as we’ll discuss) that would create the illusion of height, they’re encoded in binaural stereo, so any pair of headphones or earphones will work. I reached out to David and Brent to find out more about the album and spatial audio in general. If you want to read more about the album itself, I review it in greater depth after the interview.

How did this album come about?

David Chesky: I have a new company, The Audiophile Society, where we create dedicated mixes for headphones, sold as downloads in DSD or PCM. Since we were already producing these, I thought it would be a great idea to create a test album/download as a tool for those interested in learning more about headphone listening. Approximately 99.999999% of all albums are mixed on two speakers in a recording studio, leaving headphone users to adapt as best they can. But what if we made a special mix designed specifically for headphones, externalizing the sound to create a much better experience? These headphone mixes are unique and should only be played on headphones; they’re not meant for speakers. However, we also include speaker mixes for those who prefer them, ensuring each is played back on its correct platform.

David Chesky

David Chesky

Brent Butterworth: David called me in January with the idea to do a headphone test disc for his latest venture, the Audiophile Society, that would incorporate spatial audio tests—specifically for headphones, not for home-theater systems. He knew it would require generating some complicated test routines. I’d worked with him previously on DVD-Audio and SACD test discs, plus some other productions through the years, and I’d recently mixed a jazz album of my own that he liked. So he thought we might be able to work together and figure out how to do this.

For about three years, David’s been doing his own Mega Dimensional Sound releases, where he mixes everything in a digital-audio workstation and does his own processing to get an immersive effect from headphones, without using Dolby Atmos or DTS:X or anything like that. So he wanted to incorporate some of that, too.

How long did it take to complete?

DC: Brent and I worked on it throughout the summer, experimenting with new ideas, tests, and adjustments. In total, it took about six months to complete.

What aspect of working on it did you find most interesting? Were there any unexpected challenges?

DC: Comparing Dolby Atmos to Apple Spatial Audio was fascinating. The hearing tests included at the end of the album are a nice touch, allowing listeners to assess their hearing quality.

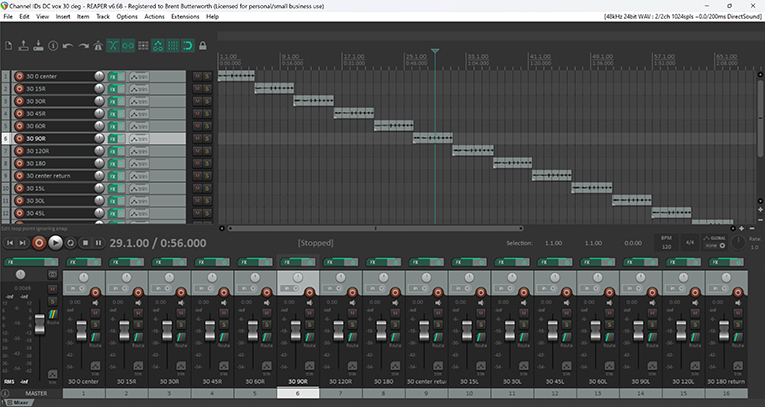

Brent Butterworth

Brent Butterworth

BB: Having to learn to mix in Atmos. I’d seen it done but never actually done it myself. So I started out using a Fiedler Audio Atmos plug-in in Reaper, which is the DAW (digital audio workstation) I mostly use. But I ran into some limitations, so I learned the PreSonus Studio One DAW, which has Atmos built in. Learning a new DAW is challenging. It’s like Photoshop; you can’t ever really master the whole thing or even discover all the possibilities.

And then David tried out the Apple binaural Atmos encoder, which encodes all the Atmos tracks and objects into a binaural signal that’s intended to simulate the sound of an Atmos-compatible speaker system, with front speakers, surround speakers, and height speakers. I assumed it would be basically the same as Dolby’s encoder, but David insisted I give it a listen. That meant learning Apple’s own DAW, Logic, which can use either the Apple or Dolby encoder. I was shocked at what a difference there was between the encoders. So I ended up having to learn Logic and render a lot of the material that way.

How should people use this album with their own headphones?

DC: Ideally, listeners should wear their headphones and follow along with the accompanying PDF book, repeating the tests to fine-tune spatial positioning. It’s interesting to see how well your own pinnae (the outer part of the ears) align with the tests on different headphones. This isn’t a one-time entertainment album; it’s a reference tool you can use over time.

BB: This is the best part. It’s really easy because we mixed the test material mostly in Atmos but rendered the whole thing in binaural stereo, so you can play it on any headphones, with any computer, any headphone amp, any phone that’ll play 24-bit/48kHz stereo files, or pretty much any portable audio player. You don’t need Dolby Atmos or DTS:X or any special processing. It’s all baked in.

You can use it to test different headphones to see how well they reproduce spatial sound for you. We found the differences among headphones when reproducing spatial material can be large, and they’re also unpredictable because the head-related transfer function (HRTF) that our brain and ears use to locate sounds is different for everyone, because our pinnae, ear canals, head shapes, etc., are all different. So the results that you get will almost certainly be different from what someone else gets.

We have a whole bunch of test tones on there with specific callouts for different points in space, like “45 degrees left, 30 degrees up.” We do sweeps around you, overhead front to back, overhead side to side, and so forth. So it’s very easy to tell exactly what’s going on, which is not true when you’re listening to Atmos music tracks.

And we have demos showing the differences between the Apple and Dolby encoders, and comparing those to David’s Mega Dimensional Sound. So you end up understanding spatial audio for headphones in far more depth than you could just by listening to Atmos tunes on Apple Music.

What is something people should know about the album?

DC: Learning about spatial positioning on headphones is eye-opening. Unlike speaker setups, which are limited to a 60-degree triangle, headphones offer a much broader audio palette. The challenge for musicians and producers is to fully utilize this expanded space, rather than keeping the sound centered between the ears. This album isn’t just about sound quality; it’s educational. It can reveal insights about your current headphones—or ones you’re considering purchasing—and offers knowledge I gained through the production process with Brent.

BB: The motto of this project turned out to be “Your results will vary.” We did months’ worth of experimenting with different test tones, different recordings David and I had done, and different mixing and rendering tools. And we’d send out files to people who we knew would give them a careful listen—reviewers and recording engineers, mostly. [Full disclosure: I was one of these folks, but I wasn’t told about the specifics of the project.] It was frustrating because people reported such different results.

We were expecting to come out with more definite conclusions like, “These headphones are better for spatial, and these don’t work so well,” but we realized that the true utility of this is to find out what headphones work best for you.

And to understand what the limits of spatial audio technologies are with headphones. Dolby and Apple are promising a universally wonderful result, but in my opinion, listening to Atmos music tracks through headphones is always something less than listening to an Atmos speaker system. With this album, you can find out how much less, and what will get you closer to that ideal spatial-audio headphone experience. This is important if you’re into immersive sound, because almost all the listening to Dolby Atmos music tracks will be through headphones.

Anything else (random or otherwise) you’d like to add?

DC: I hope headphone enthusiasts support this movement toward dedicated headphone mixes. Think about it: with a quality pair of headphones, a preamp, and a DAC, you can achieve ultra-high-resolution sound for about one percent of the cost of a large, high-end audiophile setup—without the room-acoustics challenges that come with traditional hi-fi systems. For the past 70 years, we’ve made records the same way for both headphones and speakers. It’s time to try something new and push boundaries, even if it means we might occasionally fall short.

BB: We added ten of the Audiophile Society’s Mega Dimensional Sound recordings at the end. I assumed David would choose them, but he insisted I pick them. So I had to go through almost all the Audiophile Society releases, and while I’d heard several of his earliest immersive headphone recordings, there were some newer things I found that were mind-blowing.

My favorite is the track “Forças de Natureza” by Café. I think if the people at Dolby and Apple listen to this, they’ll try to reverse-engineer what David did, or maybe just call him up and bug him to reveal his secrets. There’s part of this test album where I try to use Atmos to replicate what he’s doing, and I think people will hear that he definitely has some things happening that the big tech companies haven’t figured out yet.

The album

The album’s tracks span three broad categories: basic tests, spatial audio tests, and songs that show off spatial audio (mixed with Dolby, Apple’s encoder, or Chesky’s Mega Dimensional Sound). Many of these also have an intro track that explains what you’re about to hear and what to listen for. As an example, the first test is for phase. David tells you that his voice should sound inside, or directly in front of or behind, your head. Then it switches to out-of-phase, and he explains how it should sound “spacey,” like it’s not coming from anywhere. Easy to understand, right? It’s also a logical place to start, since if this is wrong, everything that follows is likely going to be messed up.

Next is a series of “channel ID tests,” which have David moving around the soundstage, saying where he should sound like he’s coming from. For instance, he’ll say “fifteen degrees right,” and yep, he sounds like he’s just off center. This continues all the way around your head. This album is primarily about spatial audio though, and that’s when things get really interesting. These channel IDs are repeated, but using height. So, 15, 30, and 45 degrees above the “0 degree” plane of your ears. These tests are fascinating because it’s entirely possible (perhaps likely) that you’ll get different results using different headphones or earphones.

For me, the most telling tracks were the left-to-right overhead passes. These were encoded with either the Dolby or Apple binaural encoders. As expected, I got different results with open-back, over-ear HiFiMan Sundaras compared to Meze Advar in-ear monitors. While both did pretty well, the Advars had a more realistic “directly above my head” position. Neither had a totally convincing 180 degrees behind. At least that’s how they sounded for me. There are no wrong answers here. As mentioned, everyone’s ears and brain vary, and so the way they interact with different headphones is going to vary too. This is about figuring out what works for you, or how well your headphones work on your head when it comes to spatial audio.

Going beyond tests with a moving voice, next up on the album is the same song encoded using the Dolby encoder, Apple’s, and then Chesky’s own Mega Dimensional Sound. It’s fascinating how the same idea, “spatial audio,” can sound so radically different. One has more of a convincing height effect, one is more diffuse, and one sounds altogether “bigger” than the others. At least with my ears and the headphones I was using. I’ll let you decide how they sound with your gear.

Next is a series of high- and low-frequency test tones to see how capable your headphones and ears really are. Don’t get too despondent if you can’t hear some of the highest tones. Most adults have some hearing loss, and if you spent your youth going to concerts without earplugs, you might have more than some. Also, there are no headphones with perfectly flat frequency response. Regardless, it’s probably worth getting your ears professionally checked anyway, so you’ll have a baseline for later. The high-frequency tests might give you the motivation to do that.

Lastly, there are 10 tracks from the Audiophile Society’s vault. These are all in Chesky’s Mega Dimensional Sound. I think these are great, not just for being well recorded (no surprise there), but also for showing what’s possible with spatial audio recording. The sense of space, of being with the musicians in a real place, is noticeably different compared to a traditional mix. For certain kinds of music, it definitely adds something to the experience.

More than anything, I found this album quite eye-opening. I’ve written about spatial audio for years and have come away unimpressed from most of my reviews of the technology. Part of it is that the marketing focuses too much on the gimmicky hardware aspect, where “head tracking” keeps sound focused on one place when you move your head. Easy to demo, hard to find useful. That’s the problem with such a broad term like “spatial audio,” because it also encompasses audio that this album so impressively shows off. Audio that’s specifically encoded for spatial sounds, which can work well . . . sometimes. That’s what was so interesting, how much your own ears and gears affect the effect. It’s just two speakers, remember, right on (or in) your ears. So all of this height stuff is particularly clever, at least when it’s done right. Hearing it done right, in both an analytical and practical way, is definitely the beauty of this test album.

The Headphone Evaluation and Spatial Audio Test Album is available for purchase from the Audiophile Society’s website.

. . . Geoffrey Morrison