Some studies have shown that tastes in music solidify when you’re young and rarely change. Some say your musical interests lock in during your teenage years. Basically, once you’ve settled on what you like, that doesn’t change once you hit adulthood and middle age.

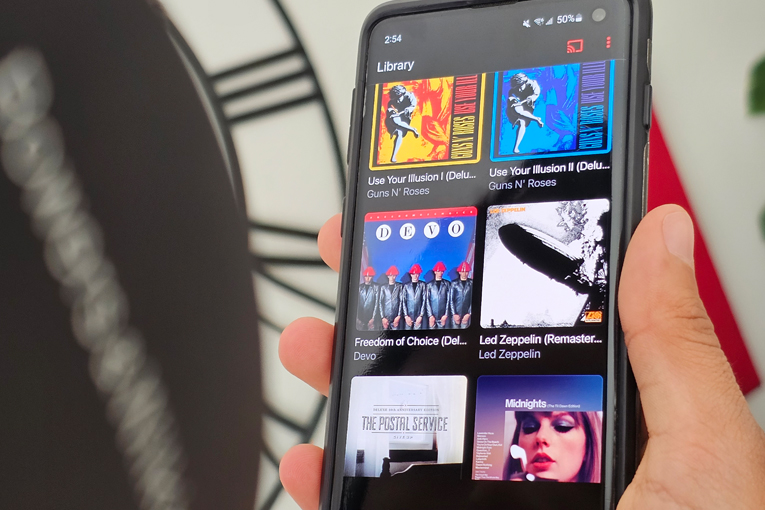

Anecdotally, this certainly explains the opinion I’ve heard for years: “there’s no good music these days.” I was lucky enough to start in this industry very young. Fresh out of college, I’d hear sentiments like that from old-guard audiophile types. I’d bristle at the idea. How could you not like the Postal Service or the Killers? I was determined not to end up like that. I always prided myself on my eclectic taste in music, and it was important to me that I held on to that broad range of musical interests.

Time is a relentless beast, and as I now approach the age of those middle-aged reviewers from when I first started, I’m proud to say my tastes are still wide ranging and decidedly eclectic. Or are they? Have I fallen into the same trap and just not noticed?

I’d always figured the solidification of musical tastes was a narrow one. Which is to say, that once someone reached a certain age, they only listened to the same bands from that point on. They didn’t try anything new, even within the same genre. To an extent, this is accurate. There are people who only listen to the same core bands, and those are the bands they loved when they were young. I believe these are the folks most likely to espouse the “there’s no good music these days” mindset. To them, that’s true. Maybe it’s because their favorite bands broke up, or they stopped putting out good music, or best case, they have a far slower output compared to when they were young (this isn’t a subtle dig at the Rolling Stones—good for them). Music today isn’t what they had when they were young. Music changes. So do people.

My thoughts on this phenomenon are changing too. The average listener might develop a “no good new music” mindset, but I think many audiophiles strive to find new music all the time, and they probably listen to new artists on a regular basis. Could we as a group—and I include you, dear reader—dodge this calcification of taste as we age?

I had a bit of a shock recently after stumbling on yet another article about this phenomenon. I’d succeeded, I arrogantly thought, in reaching middle age with my desire for new music intact. After all, I listen to new music all the time. And then I had a horrifying realization: while I do constantly seek out new bands and new musical experiences, I don’t seek out new genres. The core features I look for in a song haven’t changed in a long time. My love of melody, certain instruments, certain types of voices, has, I had to finally admit, solidified. I wasn’t a big fan of hip hop or pop country in my youth, and I’m still not. I like bebop but not fusion. I like Bach but not Schönberg. None of these things have changed since I was, gulp, younger. I like a “type” of song that might be by different artists, in different styles, even in different genres, but that “type” has unquestionably solidified. Is it possible that I, despite my belief I was above it, have also succumbed to this solidification phenomenon? Am I, who spent so many years as the youngest audio reviewer in the room, getting older?

Perhaps that’s what the issue actually is: aging, or more specifically, a fear of it. As people age, there’s a natural tendency to become less open to trying new things. They like the safety and comfort of what they know. The mental effort to try something new gets more and more difficult. I don’t want that to happen. Maybe it doesn’t have to.

You probably can’t force it. I doubt you could listen to Tibetan thrash metal on repeat for a week and turn yourself into a fan. Maybe that’s OK. None of us are under any obligation to like anything we don’t want to like. If all you want is to listen to the Eagles all day every day, you do you. I’m not here to yuck anyone’s yums. But being open to trying things that are different from what you like, or at least what you’re used to, is probably a good thing.

More to the point, if you find yourself feeling that “new music” is trash or that bands now aren’t as good as your favorites, it’s worth asking, “Is this thing I like actually good, or was I just 14 when it came out?” Maybe the thing you like is good. Maybe the new thing you don’t like, that is liked by current 14-year-olds, is also good. Maybe both are only good to the people that like them. That’s OK too. It’s a big world out there. We can like different things.

. . . Geoffrey Morrison